IPv6+Ruby part 2: IPv6 and web applications

Table of Contents

This post is the second in a series about IPv6 and why it matters. If you are interested in the details about what IPv6 is, please read the first post. If you already know why it is important and just want to know how to use it, continue to the next post. All links are at the bottom of this post.

The world is running out of IPv4 addresses. By now, you have likely heard someone say that more times than there are IPv4 addresses, but for some reason we have not all died yet (though it would explain a lot about 2020). Why is that, and does IPv6 really affect you as a developer?

I’m a web developer, why should I care?

You are developing web apps and are deploying them on Heroku or some other platform and they do not have IPv6 support. What does that mean for you? In all likelihood, there should be no problem for most of your users accessing your site, but some of them, especially some mobile users, can have problems.

So why is that?

Well, as we established before, we have kind of run out of IPv4 addresses. This is not a huge issue for a lot of established ISPs with tons of addresses, but as new services emerge, they will have less access to IPv4 addresses. Many mobile networks, especially in the APAC region and in the U.S., have been deployed as IPv6 only mobile networks.

Getting an address to connect to

A bit of background to begin with. Usually, when a computer wants to access

a website, it only has a name like gitlab.com and nothing else. Computers

use the Domain Name System (DNS) protocol to convert these human readable

names into IP addresses. I will not go into details about DNS, but there are

two kinds of answers we are looking for:

IN A— Answers containing an IPv4 addressIN AAAA— Answers containing an IPv6 address

We can use the UNIX tool dig to see this in action asking for IPv4 and IPv6 for the same (IPv6 enabled) site:

$ dig gitlab.com A

[...]

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;gitlab.com. IN A;;

ANSWER SECTION:

gitlab.com. 88 IN A 172.65.251.78

[...]

$ dig gitlab.com AAAA

[...]

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;gitlab.com. IN AAAA;;

ANSWER SECTION:

gitlab.com. 198 IN AAAA 2606:4700:90:0:f22e:fbec:5bed:a9b9

[...]

Your computer basically does this in the background whenever you want to

connect something using the domain name (like gitlab.com).

How does an IPv6 only user access the legacy IPv4 internet?

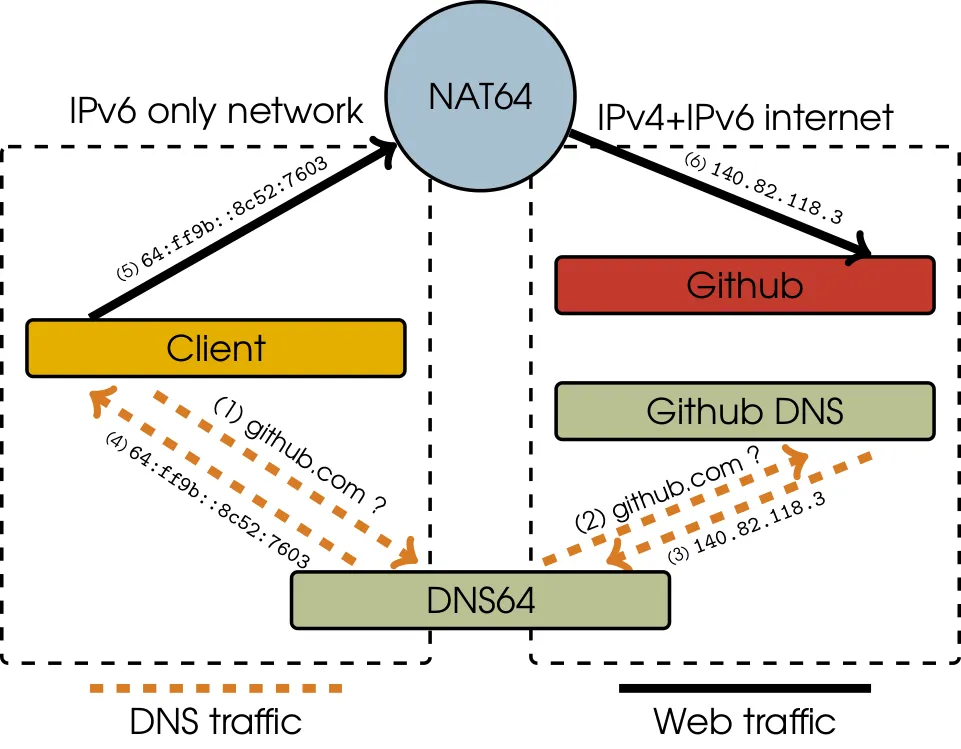

Instead of giving all their users an IPv4 address or maybe using Carrier-grade

NAT, some ISPs will deploy NAT64+DNS64 for accessing legacy services like

github.com that only exists on the IPv4 internet. A very simplified version of

what is happening is:

- Give all users an IPv6 address only.

- Make sure you control all DNS requests in your network.

- When someone makes a DNS request for something that only exists on the old

IPv4 internet, give them a fake DNS AAAA response with the IPv4 address of

what the user is trying to reach, embedded into the IPv6 address in the

64:ff9b::/96network. For example, Github resolves toIN A 140.82.118.3which will becomeIN AAAA 64:ff9b::8c52:7603, where8c52:7603is the same 32-bits as140.82.118.3, with the former being in HEX. Now the client in the network will send traffic for Github to64:ff9b::8c52:7603. - When receiving a packet leaving your network with a destination of somewhere

in the

64:ff9b::/96network, you know it is a fake IPv6 address with IPv4 embedded. You then translate the IPv6 packet into IPv4 and send it out your network. - Keep the state of these mappings (just like in NAT), so you know what to do with the response traffic coming into your network which is just translating back into IPv6.

Simple, right? ………

When accessing IPv4 services from an IPv6 only network, a client has to look up a domain via a DNS64 server that will answer with a translation prefix IPv6 address. Then as the client’s traffic leaves the network, NAT64 will be used to translate the traffic into IPv4 and vice versa with response traffic.

Depending on your web app, you might make one HTTP request, render everything on the server, send it back to the user, and then, done. But you might also request the main site, load a style sheet from another location along side a bunch of images and JS that will in turn go out and pick up resources as the user browses the website. Doing 20+ requests to 5 different endpoints is not really that strange today. All of these requests will require NAT64 & DNS64 translations, becoming even more time consuming. Github alone has over 40 requests from my browser.

There is another catch and it is an important one. Some protocols have chosen to embed IP literals into their packets. This means using an IP address inside the payload of the packet itself, most often an IPv4 address. This can lead to connection issues with NAT64 users and should be avoided. Some of these protocols are: SIP, SDP, FTP, WebSockets*, and P2PP. There are real world examples of applications using IP literals in their packets not working on NAT64 networks:

- https://github.com/ValveSoftware/steam-for-linux/issues/2912

- https://github.com/ValveSoftware/steam-for-linux/issues/3372

*: WebSockets confusion

When doing the research for this article, I came across both the Apple documentation as well as the Wikipedia article saying that WebSockets does not support NAT64. My guess is that this was first added to Wikipedia (back in March 2014), and then later someone at Apple just copied over the list. Doing some Wireshark dumps leads me to say that there should not be a problem with WebSockets and NAT64 unless you connect directly to an IP address instead of a hostname because of the

Host: [host/ip]header. This header also exists in HTTP and will at most times also break with NAT64 if you put in an IPv6 translation address.

The Steam Client errors linked above are still real, but maybe Valve has done the wrong thing and used IP literals in their header.

If you have more insight on this or if I have missed something, please let me know, and if you are looking for more on how WebSockets works, you can check out: https://www.honeybadger.io/blog/building-a-simple-websockets-server-from-scratch-in-ruby/

Ok, back to the post!

What do I gain from supporting IPv6?

So besides not breaking some key internet protocols with NAT64 clients and keeping the world from running out of IP addresses, there are other advantages of supporting IPv6.

Improved page rankings and SEO

While you might be deploying your service in a state of the art data centre that can support large volumes of traffic with low latency, you cannot control the ISPs that your users use. This means that the latency introduced with NAT/NAT64 is out of your control. Google is ranking pages based on load times, and if your site loads slower for mobile users compared to competitors’ sites or does not work at all because of NAT64, it might affect your SEO.

Apple reports connection times with their devices on IPv6 being 1.4 times faster than connection times on IPv4. This could be because of multiple things, but the main factors are likely newer hardware on the networks that have deployed IPv6, and not having the latency of normal IPv4 NAT or NAT64.

Direct connections by removing the need for NAT

Right now, almost all of your IPv4 users are behind NAT. If you are developing IoT devices and want to be able to communicate directly with these devices in peoples homes, getting rid of NAT and Carrier-grade NAT by using IPv6 will make that communication easier and more reliable.

Protocol advantages with IPv6

IPv6 has been designed with a number of improvements in mind:

- Efficient route-aggregation in routers helping the internet grow.

- Path MTU discovery. IPv6 will find the MTU of the connection. This moves all segmentation of packets to the source of a packet instead of happening in an inline router as with IPv4.

- Build in IPSec for better security. This does not mean that all connections are automatically encrypted, but does make IPSec easier compared to IPv4 in some instances.

- Larger multicast address space, and better multicast routing. ISPs still need to gain better multicast support generally though, but this is a step in the right direction.

So what do I do?

First of all, get IPv6 on your application! Maybe you are using a hosting provider that does not support IPv6 and should then consider what consequences that is having for your users. This could depend on what protocols you are using in your application. Send an email to your provider and tell them that you need IPv6 and that it is not okay in 2021 to not have any IPv6 support, a protocol that was standardized in 1998.

Secondly, do not use IP literals in your messages between you and your user. Not in HTTP requests, not in your own protocol, not ever. Also, do not use IP literals for keeping track of your users. If you need some connection tracking, give your user a token they can send along with their requests or something like that. You do not know anything about the network that is between you and your user, so take control of what is happening instead of assuming that you have the full picture. This might have the added benefit of giving your users an easier time when roaming between networks.

Lastly, if you have database fields containing IP addresses as either bits or strings, make sure that they are wide enough to support IPv6 addresses.

Is it really that easy?

Well, it depends. If you have a single application running somewhere and you can get IPv6 on it, that is great, but a lot of deployments are a lot more complicated than that. If you have a bigger deployment, you likely have some kind of network team, or maybe just that one person who understands a bit more about network. Talk to that team/person and figure out how you can get IPv6 deployed together.

Is there any good news?

Sure, or at least interesting news. If you go to Google’s IPv6 statistics and look at just 2020, you can clearly see that people started working from home because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Usually, the weekends when people are home is the time with the most IPv6 traffic, as corporate networks are lagging behind in the IPv6 adaptation. With a ton of people working from home, the difference between weekday and weekend is a lot smaller.

There is also Facebook that does IPv6-only inside their data centres, and then support legacy IPv4 at the edge of their networks. Supporting two network stacks on their infrastructure is not great, so they have opted not to do so to make their network simpler. This is not really a “new” thing, but I felt it was important to touch upon anyway as this is a good choice for IPv6 adaptation.

Doing IPv6-only networks with IPv4 translations on the edge is definitely going to be one of the major ways IPv4 will be supported in the future, as the overhead of running two IP stacks is not the best long term solution. Running dual-stack is a good way to start the migration to make sure everything works with IPv6 though!

Wrapping up

You now know why you should think about IPv6, and what consequences of not using IPv6 could be for your customers and in turn for your business.

In the next instalment, we will dive into dual-stack sockets with the Ruby programming language, giving an example of how to support IPv4 and IPv6 at the same time.

This article is part 2 in a series consisting of:

- IPv6+Ruby part 1: Introduction to IPv6

- IPv6+Ruby part 2: IPv6 and web applications

- IPv6+Ruby part 3: Dual stack (IPv4+IPv6) TCP sockets

- IPv6+Ruby part 4: Dual stack (IPv4+IPv6) TCP sockets

- IPv6+Ruby part 5: Service discovery with IPv6 and Multicast

References

- https://www.google.com/intl/en/ipv6/statistics.html

- https://developer.apple.com/library/archive/documentation/NetworkingInternetWeb/Conceptual/NetworkingOverview/UnderstandingandPreparingfortheIPv6Transition/UnderstandingandPreparingfortheIPv6Transition.html

- https://engineering.fb.com/production-engineering/legacy-support-on-ipv6-only-infra/

- https://developer.apple.com/videos/play/wwdc2020/10111/