IPv6+Ruby part 1: Introduction to IPv6

Table of Contents

For many years, people have been talking about the Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6). There have been “World IPv6 day”s and companies like Apple have made rules about applications published via their app store needing to be IPv6 compatible. But what does all this mean and what is IPv6 really?

In this article series, I am going explain the value of knowing what IPv6 is, explore basic IPv6 concepts, and dive into the usage for software developers.

This first part will tackle network basics, the history of IPv4, and what IPv6 is. The second part will talk about why you as a software developer need to pay attention to and understand IPv6.

The third part explains how to implement a server application with IPv6 and Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) in the Ruby programming language, before part four dives into the same application but with User Datagram Protocol (UDP). Lastly, part five will go into multicast and service discovery with Ruby and IPv6.

Even though the examples given in the last three parts are written in Ruby, the ideas should be simple enough for developers not familiar with Ruby to follow.

Feel free to skip ahead if you know your basics:

- IPv6+Ruby part 1: Introduction to IPv6

- IPv6+Ruby part 2: IPv6 and web applications

- IPv6+Ruby part 3: Dual stack (IPv4+IPv6) TCP sockets

- IPv6+Ruby part 4: Dual stack (IPv4+IPv6) TCP sockets

- IPv6+Ruby part 5: Service discovery with IPv6 and Multicast

Quick network introduction — The OSI model

When talking about network protocols, the OSI model is a great tool to visualize the different layers of the protocol stack. The OSI model has seven layers, though to keep things simple the Presentation and Session layers will just be denoted as OS.

OSI model showing the path of data down through layers, across networks, and up through the layers at the other side. Note that the Session and Presentation layers are combined into the single OS box here.

- Application — Where your web browser, your server, and your video game lives.

- OS — Keeping track of things not that important to us right now.

- Transport — Protocols such as TCP and UDP live here.

- Network — IPv4 and IPv6 lives here.

- Data-link — Media Access Control (MAC). These are protocols for the physical mediums like a cabled Ethernet or Wi-Fi.

- Physical — The cable (copper/fibre) or Wi-Fi (electromagnetic waves in the air) itself.

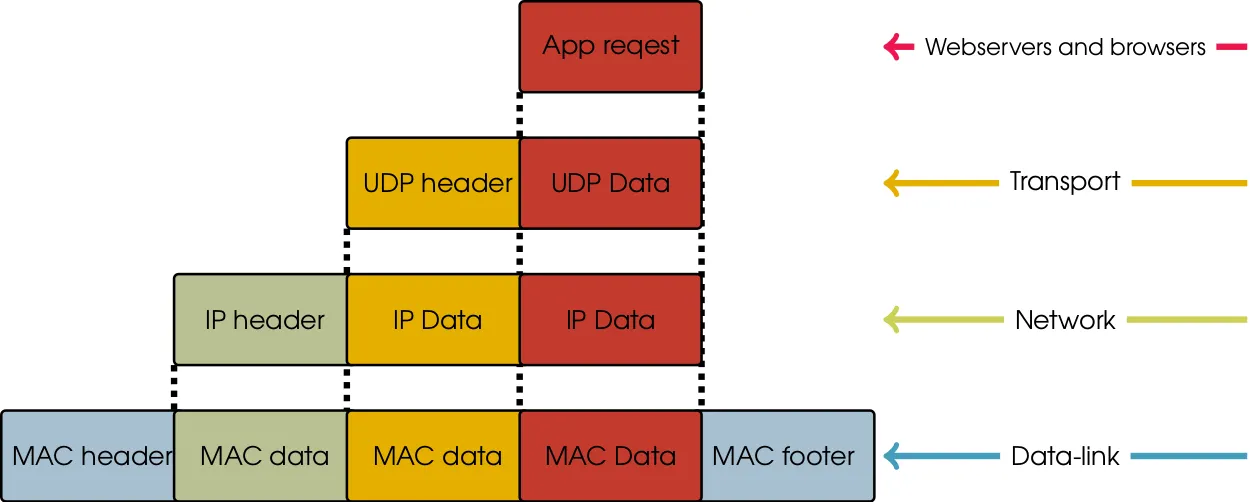

When you want to send something over the network, your data will go down through all the layers in the protocol stack. Each of these layers will add some kind of information to the data.

- Transport — TCP or UDP will add a header with source and destination ports to your data. This is like telling you which door you have to go through, but not at which address that door is.

- Network — IPv4 or IPv6 will add a header with source and a destination address. This is like adding the final street address you should end up at, but with no information on how to get there.

- Data-link — Will add a header with source and destination MAC addresses. This is like having someone tell you the next intersection to go to, based on the current intersection that you are in. A footer with a checksum is also added to the frame.

- Physical — Ethernet and Wi-Fi. The roads in this analogy.

While TCP/UDP ports and IP addresses are something that can be configured dynamically, MAC addresses are tied to the physical network interface, and should in theory never overlap as they are controlled from a central body.

Again, this is an oversimplification but it is important to know a piece of information is added to your data at every point in this layered structure, and you need them all for anything to work!

When you send data, you start with the “App request” in the figure below. You then move down through the layers, adding headers in each of them. When you receive data, you start with the full MAC frame and peel off headers as you go back up to the application layer, perhaps with a response to the “App request”.

Going down through each layer, the previous layers information is just regarded as “data” as only the headers (and footer) are relevant in the given layer.

Very simplified history lesson of IPv4

IPv4 was introduced back in 1981 in [RFC791][rfc791] and deployed in 1983 in

the ARPANET for production. The written format of the IPv4 address is called

dotted-decimal and consists of four decimal numbers between 0 and 255

separated by a dot (.). This could be something like 192.168.0.213. This

represents a 32-bit number (each of the four numbers are 8-bits), and thus

theoretically gives us access to 2^32 IPv4 addresses or around 4.2*10^9

addresses.

The address space back then was divided into five classes (A, B, C, D, E) and

each of these classes had a fixed size network. A class A network had

16,777,216 addresses, class B networks had 65,536, and class C networks had

256 (D and E are special, so forget about them for now). As an example,

192.168.0.213 is an address in a class C network that would contain addresses

from 192.168.0.0 to 192.168.0.255.

A total of 128 class A networks; 16,384 class B networks; and 2,097,152 class C networks existed for the entire internet.

It was discovered that having these fixed size networks was a bad idea, as

available address space was rapidly shrinking. Thus, in 1993, Classless

Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR) (RFC1517) was introduced. Now a network

had a network address and a subnet mask defining the length of the network,

being between 1 and 31 bits. This can be notated as 192.168.0.0/16 where the

16 is the subnet mask and represents how many of the first bits of the

address is the subnet or “fixed” so to speak. Here the 16 first bits are

covering 192.168, making the network span from 192.168.0.0 to

192.168.255.255.

Introducing CIDR helped slow down the exhaustion of IPv4 addresses but not enough, as many more hosts were starting to access the internet. Thus, in 1999, Network Address Translation (NAT)(RFC2663) was born, making use of private IP address (RFC1918). This ensured that an Internet Service Provider (ISP) could assign only one IPv4 address to a customer, but that the customer was able to still get multiple hosts onto the internet by using private addresses inside their networks and share a single public address using NAT. This, however, broke the “end-to-end principle”, as any node in the internet could no longer directly address another node.

At the same time in 1998, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) had defined the successor to IPv4. This successor is IPv6.

IPv6, the internet of tomorrow from 1998

IPv6 first of all introduces a lot more addresses. Remember, IPv4 theoretically

had 4.2*10^9 addresses in a 32-bit address space. IPv6 uses a 128-bit address

space, and has 2^128 or around 3.4*10^38 addresses available. The actual

number is 340,282,366,920,938,463,463,374,607,431,768,211,456.

IPv6 is represented as eight groups of four hexadecimal numbers divided by a

colon (:) and looks like: 2001:41d0:0701:1100:ef8a:91df:5cba:29c8. Just like

with CIDR in IPv4, we can describe a network by using the CIDR notation, and

putting the network length in the end of the address like

fe80:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000/64.

IPv4 uses broadcast for learning MAC addresses and getting an IP address. IPv6 uses self-configured link-local addresses and multicast instead, and does so in a very elegant way compared to IPv4.

Very importantly, IPv6 gives back the end-to-end principle that we all grew up without having. Imagine not having to think about what “NAT type” your network is running when you want to play online games, but instead being able to just address your peers directly with some coordination.

On top of that, some of the protocols that felt kind of shoe-horned into IPv4 (I’m looking at you DHCP) were baked into IPv6 (mostly) from the beginning.

IPv6 Address shortening

Instead of writing the full IPv6 address for some host, you can represent IPv6

addresses shorter if you want to. As an example, instead of taking

wikipedia.org and looking at its full address:

2620:0000:0862:ed1a:0000:0000:0000:0001

It can be shortened to:

2620:0:862:ed1a::1

This is done with three rules:

- Consecutive groups of zeros (separated by colons) can be shortened to

::. Here that makes0000:0000:0000into::. This can only be done once though. - Leading zeros can be omitted. This makes

:0862:into:862:and:0001into:1. - Groups of only zeros that has not been shortened by the first rule, can be

shortened according to the second rule down to

:0:.

Using IPv6 in a browser

You have very likely at some point had to type in an IPv4 address in a web

browser to access some development site or similar. You can also do that in

IPv6, and all you have to do is add square brackets around it like

http://[2001:41d0:701:1100::29c8]/. However, you might prefer to ensure your

devices have DNS instead.

IPv6 special addresses

IPv4 has addresses you just have to be familiar with. The same goes for IPv6 and they are as follows:

::1- Localhost - This is your own computer.127.0.0.1in IPv4.::- Everyone - This is like0.0.0.0in IPv4.

IPv6 and privacy

I have a feeling someone might be sceptical if I do not address it, so here it is. Over the years, there have been a lot of privacy concerns with IPv6 — mostly that you would be either globally traceable, or that you would not be able to hide behind a layer of NATs. Let us start with the issue of global traceability.

Devices like your phone or computer use a protocol called SLAAC to obtain an IPv6 address a DNS server in order to access the internet. In early versions of SLAAC, the lower part of the IPv6 address a host took was based entirely on the MAC address of the network interface. This would mean that no matter where you went in the world, the last 64 bits of your IPv6 address would always be the same. This makes tracking very easy and is a bad thing! RFC4941 was introduced to avoid this, by letting the host pick a random address instead. That infuriated many network administrators since hosts were getting new addresses every time they connected, so a scheme for generating a random interface identifier per network was introduced with RFC7217. This ensures you have a stable address within a network, but also that you will have a completely different address in another network.

Great, now to the hiding behind NATs part. The short answer is, your computer can leak its private RFC1918 IPv4 address via a number of protocols, especially via your browser. eBay is using software to scan your entire local network when you visit their website. NAT Slipstream attacks was the big new thing last year allowing connections to be made through NAT from the outside, and more attacks like it will surely follow. If you are feeling safe behind a NAT, you should stop feeling that! On top of that, depending on where in the world you live, governments might mandate logging of local addresses to sessions. Using NAT will not hide you, so please use something better if you for some reason need to stay hidden!

So is IPv6 all fun and games?

Well, there are some issues! There is legacy network equipment that does not support IPv6 and needs to be changed, though this should all be fairly old and very power inefficient equipment anyway — changing it might generally be a good idea. Some software also have issues with IPv6 or do not support it at all, though this is where you as a programmer can make a change.

IPv4 and IPv6 will need to co-exist, giving people the time they need to transition from IPv4 into an IPv4+IPv6 environment (called dual-stack). In the future, we can start getting rid of IPv4 completely. However, there are some tricks to run IPv6-only inside your network and translate to IPv4 at the edge of your network. More on that in part 2 of this article series.

Basics done, now comes the fun part

You are now a master of basic computer networking. Or, at least you might know a bit more about it now than you did before. Again, this is a very brief introduction, and I have skipped a whole lot of things that make the internet work. You should now know enough to dive a bit deeper into the topic and perhaps start to experiment with it.

The next part in this small article series will be on why you, as a developer or business owner, should care about IPv6. I hope to see you there!

Also, in case you think it could be interesting going into more detail on some of the network and protocol things I covered briefly in this post, please let me know and I might make a post about it in the future.

This article is part 1 in a series consisting of:

- IPv6+Ruby part 1: Introduction to IPv6

- IPv6+Ruby part 2: IPv6 and web applications

- IPv6+Ruby part 3: Dual stack (IPv4+IPv6) TCP sockets

- IPv6+Ruby part 4: Dual stack (IPv4+IPv6) TCP sockets

- IPv6+Ruby part 5: Service discovery with IPv6 and Multicast